Study Guide

HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE

The Arkansas Rep is providing this study guide to aid educators in connecting classroom activities to the musical. Information from sections 1-6 (“Note from Playwright,” “Conversation with Director,” “Structure of the Musical,” “The Folk Tales, etc.,” ”Important Dates in Production History,” and “The Authors”) contain information that should be discussed prior to viewing the musical.

The sections which follow (7-8) can be used to heighten the viewing and educational experience after watching the musical.

1. Note from Playwright in Residence

2. Conversation with Director, Addie Gorlin-Han

3. The Folk Tales, the Fairy Tales, and Possible Origins

4. Structure of the Musical

5. The Authors

6. Important Dates in the Production’s History

7. Into The Woods Trivia

1. A NOTE FROM PLAYWRIGHT IN RESIDENCE

Many people have read or watched some kind of fairy or folk tale. These tales are assumed to have been part of a culture’s oral tradition, handed down orally for years. They are often told to relay a message, gain some understanding of the universe, or to simply entertain. In the Western canon, They often begin with the memorable phrase, “Once upon and time” and end with the equally memorable phrase “happily ever after.” Although they may convey serious messages about love, loss, and society, fairytales are often funny and lighthearted. And, regardless of when they are told, fairytales and the characters in them can be shaped and reshaped to meet the needs of the various times and places in which they are told.

CANDRICE JONES

Playwright in Residence, Arkansas Repertory Theatre

The authors of Into the Woods, writer-director, James Lapine, and composer-lyricist, Stephen Sondheim, combined a few of the most well-known fairy/folk tales in the Western canon and created the musical. They cleverly interwove the tales of “Cinderella,” “Rapunzel,” “Jack and the Beanstalk,” and “Little Red Riding Hood”. For the most part, the language of the musical is reminiscent of the language and phrasing one would find in a Grimm fairy tale. They, of course, took liberties with the tales, all the while preserving the original messages the tales offered. Sondheim and Lapine questioned if the key characters from the tales had more to learn or more to desire after being granted their wishes.

One major theme that audiences should not miss while watching Into the Woods is the necessity of community. Perhaps, other than the mischievous charm that comes along with the audacity to recreate age-old tales, is also the need to find or create relevance of those tales to current times. Although the tales are old as time, Into the Woods world premiered in 1986 at the Old Globe Theater in San Diego, California. Problems individuals faced then are similar to the current problems of 2022. The AIDS epidemic was yet a mystery to the medical community and the general public. People, old and young, were dying. People old and young were losing friends. This was during the, then ongoing, United Stated – Russia Cold War. Five years following the show’s mounting, the Cold War would come to an assumed end with the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Thirty-six years later, the United States is yet grappling with not only HIV/AIDS, but the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to this, Russia’s highly publicized war activity with Ukraine had led some United States citizens to rehash conversations regarding the Cold War era.

So. Very much like in the year 1986, individuals who have suffered loss or who are reckoning with a turbulent reality may find comfort in non-traditional communities. Individuals may feel the need to find comfort in their homes as well outside of their homes. In this musical, Cinderella beautifully sings the following words to Little Red after she has suffered loss:

“Mother cannot guide you

Now you’re on your own

Only me beside you

Still, you’re not alone

No one is alone, truly

No one is alone“

The lyricist, Stephen Sondheim, wanted to express the impossibility of being alone once one finds community. Like so many television shows and theater pieces that speak to the 80s and 90s, Into the Woods is about finding stability in community even in moments of despair. This message is necessary in a world that seems more scattered than ever. People are finding community in traditional ways via family, work, and close friends. However, people are also finding community in support groups, on social media, or on the street during protests. Regardless of how or where community is found, it is important to note “No one is alone”.

2. CONVERSATION WITH DIRECTOR, ADDIE GORLIN-HAN

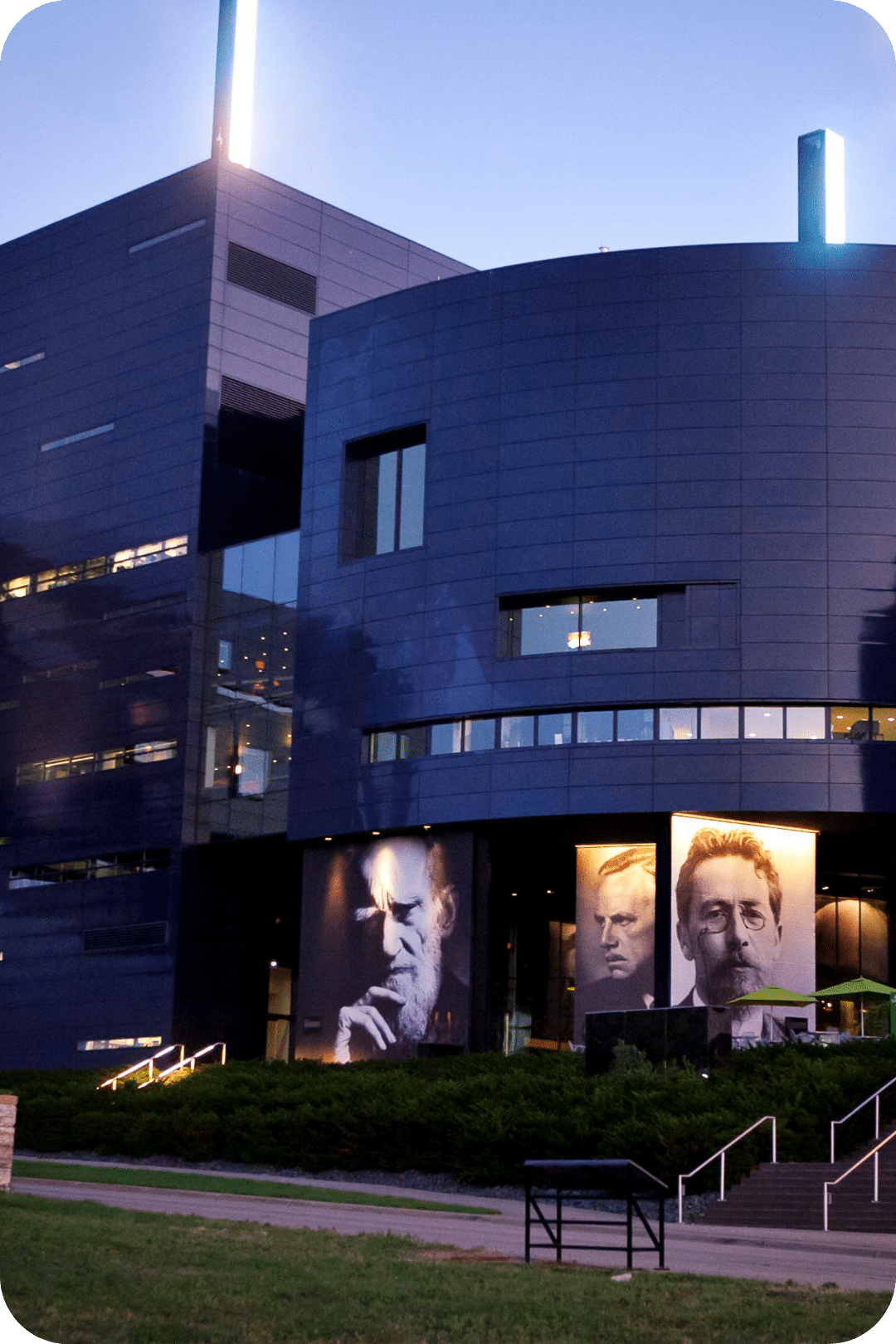

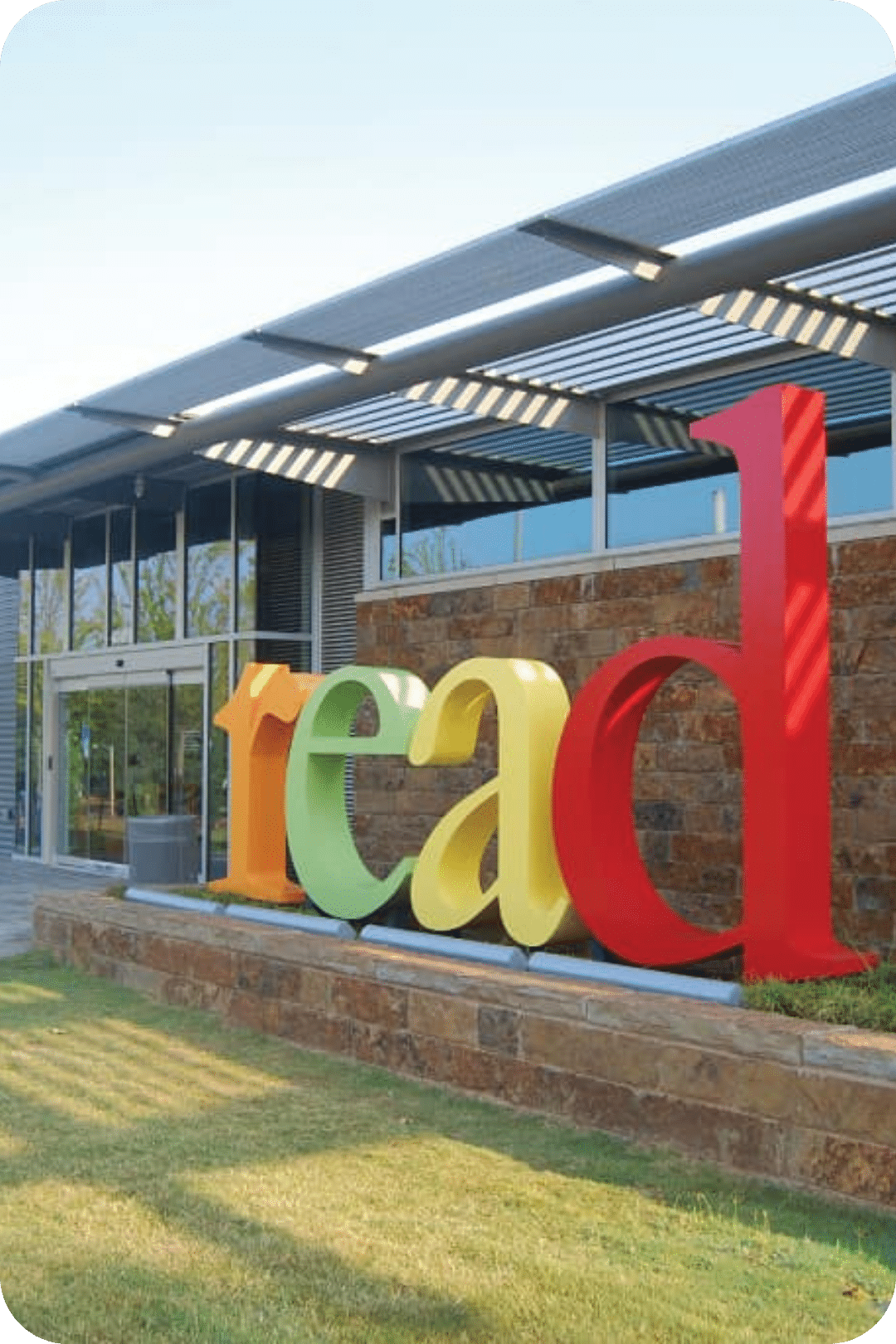

A few weeks before The Rep opened Into The Woods, playwright Candrice Jones and Into the Woods director Addie Gorlin-Han had a conversation about Addie and Scenic Designer An-Lin Dauber’s choices regarding all things theater and their scenic design which was inspired by the Hillary Rodham Clinton Children’s Library and Learning Center.

ADDIE GORLIN-HAN

Director, Into The Woods

CANDRICE JONES

How have you been?

ADDIE GORLIN-HAN

Like you, I also just had a kid. I think he’s just a month older than yours. So, I think we’re pretty parallel. I’m from Minnesota and was a freelance director and was doing shows all over and then COVID-19 and was still planning to do shows all over and then had a kid. And, then was like I need to move home. So, we moved back to Minnesota. So now, I’m Associate Producer at the Guthrie. And, I think being at the Guthrie will give me a good vantage point on what it means to be part of a theater that is part of a community.

CANDRICE JONES

So, for our Arkansas theatergoers, I’d like to get a brief on how you came to theater?

ADDIE GORLIN-HAN

I grew up acting professionally in Minneapolis in children’s theaters. Growing up in Minneapolis, if you’re a kid interested in theater, there’s so much to keep you busy and inspire you to go into the field. I also had a great theater teacher, Tom Hegg. He’s also a children’s book author. He wrote Peef: The Christmas Bear and he just inspired so many of us in Minneapolis theater. I will say I have two aunts in theater, one of which is playing Jack’s mother in this production.

CANDRICE JONES

Is this the first time you’re directing your aunt?

ADDIE GORLIN-HAN

Yes. And, she’s just so talented.

CANDRICE JONES

I listened to the manifesto you gave at Actors Theater of Louisville on “Theater for all Ages”. Can I hear your perspective?

ADDIE GORLIN-HAN

If people ask me to describe the theater that I direct, I often say I do children’s theater for adults and adult theater for children. And, that comes from a couple of things. One is I feel like theater is far more interesting if it’s intergenerational. I feel we have so many gaps in our society that actually come from a lack of intergenerational conversation. I also think if you can bring your children to the theater it’s important from a producer’s perspective because, as a mom, I’ve experienced this, it’s really expensive to pay for two tickets and a babysitter. So the more you can bring your kids to something, it can make the event more accessible. Most importantly, we [theater makers] play pretend for a living, period. Now, as a parent, I’m watching my kid play and I’m like, “playing pretend is so important.” It’s fun. We learn through play. And we learn to be more emotionally responsive and responsible through play.

CANDRICE JONES

Is this the first time you’re directing your aunt?

ADDIE GORLIN-HAN

Yes. And, she’s just so talented.

CANDRICE JONES

I listened to the manifesto you gave at Actors Theater of Louisville on “Theater for all Ages”. Can I hear your perspective?

ADDIE GORLIN-HAN

If people ask me to describe the theater that I direct, I often say I do children’s theater for adults and adult theater for children. And, that comes from a couple of things. One is I feel like theater is far more interesting if it’s intergenerational. I feel we have so many gaps in our society that actually come from a lack of intergenerational conversation. I also think if you can bring your children to the theater it’s important from a producer’s perspective because, as a mom, I’ve experienced this, it’s really expensive to pay for two tickets and a babysitter. So the more you can bring your kids to something, it can make the event more accessible. Most importantly, we [theater makers] play pretend for a living, period. Now, as a parent, I’m watching my kid play and I’m like, “playing pretend is so important.” It’s fun. We learn through play. And we learn to be more emotionally responsive and responsible through play.

CANDRICE JONES

How does that apply to Into The Woods?

ADDIE GORLIN-HAN

The musical is in a children’s library. And we [An-Lin and Addie] have taken a very playful approach. I mean for birds we’re not trying to duplicate real birds, we’re using books. We repurpose books in a playful manner. The pillow in the wolf’s bed is made of books. There’s a lyric about “flowers” and a books will open up and pop out flowers. Lots of repurposing books. And, I’m never interested in creating anything literal, so we didn’t recreate “the woods”. We have beams like the beams in the library and those are our trees. So, we’re asking the audience to use their imaginations and not be “ in literal”.

CANDRICE JONES

Could you tell me about how your process works with An-Lin Dauber [scenic and costume designer of Into The Woods]?

ADDIE GORLIN-HAN

An-Lin worked on my thesis in grad school and we’ve worked together since. So our process is we ask, “What city, what town are we doing this play in,” so we’re not taking anything for granted. And, then, oftentimes we work from there. I also always wanted to do Into The Woods in a public children’s library. So, a lot of our conversation started from there. A ton of it was researching Arkansas. So, the big orange park and the industrial elements are a huge part of the design of the Hilary Clinton library. I think honoring locality is very important.

We’ve tried to create a space that could serve as woods, so we put elements in the design that gave a nod to the library itself. Then in the second act, we take out elements of the library. That transforms it into a scarier, spookier place. We let the lights crash on stage, so they’re objects that the actors have to walk around because the characters have to deal with the consequences of their mistakes which is part of the theme of the second act.

CANDRICE JONES

Alright, that’s all my questions. Thanks so much. See you soon.

ADDIE GORLIN-HAN

See you soon.

CANDRICE JONES

How does that apply to Into The Woods?

ADDIE GORLIN-HAN

The musical is in a children’s library. And we [An-Lin and Addie] have taken a very playful approach. I mean for birds we’re not trying to duplicate real birds, we’re using books. We repurpose books in a playful manner. The pillow in the wolf’s bed is made of books. There’s a lyric about “flowers” and a books will open up and pop out flowers. Lots of repurposing books. And, I’m never interested in creating anything literal, so we didn’t recreate “the woods”. We have beams like the beams in the library and those are our trees. So, we’re asking the audience to use their imaginations and not be “ in literal”.

CANDRICE JONES

What do you think of Into the Woods having such a complicated second act?

ADDIE GORLIN-HAN

Here’s the thing. I am so frustrated when elementary and middle schools do this play and only do the first act. This happens all the time. And, I’m like, “the entire point of the play is that these stories.” Just like in real life, they don’t end in “happily ever after”. It just drives me bonkers. Because the whole action of the play is to upend this fairy tale ending. It’s about this is what it means to be human. This is the reality of the world. And it’s important for children and adults to talk about the tough things in life.

CANDRICE JONES

Could you tell me about how your process works with An-Lin Dauber [scenic and costume designer of Into The Woods]?

ADDIE GORLIN-HAN

An-Lin worked on my thesis in grad school and we’ve worked together since. So our process is we ask, “What city, what town are we doing this play in,” so we’re not taking anything for granted. And, then, oftentimes we work from there. I also always wanted to do Into The Woods in a public children’s library. So, a lot of our conversation started from there. A ton of it was researching Arkansas. So, the big orange park and the industrial elements are a huge part of the design of the Hilary Clinton library. I think honoring locality is very important.

We’ve tried to create a space that could serve as woods, so we put elements in the design that gave a nod to the library itself. Then in the second act, we take out elements of the library. That transforms it into a scarier, spookier place. We let the lights crash on stage, so they’re objects that the actors have to walk around because the characters have to deal with the consequences of their mistakes which is part of the theme of the second act.

CANDRICE JONES

Alright, that’s all my questions. Thanks so much. See you soon.

ADDIE GORLIN-HAN

See you soon.

3. The Folk Tales, Fairy Tales, and Possible Origins

There are various versions of the popular Cinderella tale with the oldest dating back to 9th century China’s Yeh-Shen. The tale of a young person who lives in oppressive circumstances until they find love and riches in the upper echelons of society is relatable across cultures. Rather than relying on Charles Perrault’s version of the tale from which Walt Disney took inspiration, Lapine and Sondheim studied the Grimm version. Lapine and Sondheim have inferred this version allowed the central character, Cinderella, an agency not found in the Perrault telling. From there, they found the characters of Cinderella’s mother whose spirit remained in a tree, the presence of the birds, as well as the use of a golden slipper.

Thought to have originated from a group of tales, “The Boy Who Stole Ogre’s Treasures,” Jack in Beanstalk has been aged at least 5,000 years. It wasn’t moralized, however, until 1807, when Benjamin Tabert introduced a fairy that offered a lesson to be learned from the tale. Sondheim and Lapine, as with all of the tales woven into the musical, exacerbated the lessons to be learned from the boy who stole from magical beings. In the musical, Jack’s exploits endanger not only his livelihood but the livelihood of all who exist in the narrative.

The origins of this story are muddled as any fairy or folk tale could be. There are two Italian origins matched to the tale. One is the tale of Petrosinella first recorded by Giambattista Basile in his collection of fairy tales in 1634, Lo cunto de li cunti (The Tale of Tales), or Pentamerone. In this collection, the tale was simply titled “Parsley”. The other is the dark, thought-to-be-true story of an Italian merchant who locked his daughter, Barbara, in a tower. Barbara had begun to practice Christianity, which was a mysterious religion in Europe at the time, and refused to marry a pagan suitor. Sondheim and Lapine clearly took from Basile’s Parsley narrative in which a pregnant woman eats the parsley from a wicked witch’s garden for inspiration.

One possible origin of this tale is an 11th-century poem from Belgium which was recorded by a priest, who says, “oh, there’s this tale told by the local peasants about a girl wearing a red baptism tunic who wanders off and encounters this wolf.” This is considered the possible inspiration for Charles Perrault’s tale of which Sondheim and Lapine took note. In the musical, the book writer and composer took advantage of Little Red Ridinghood’s tendency (found in Perrault’s tale) to disobey to create comic relief. In the end, both Little Red Ridinghood and Jack have lessons to glean from older characters about learning from mistakes, grief, and moving forward.

Lapine and Sondheim chose four well-known folk/fairy tales to weave through the plot of Into the Woods. Although people colloquially speak of fairy tales being passed down from one generation to the next, it may be best to think of folk and fairy tales as being spread from one culture to another. In addition to this people all over the world have similar experiences causing similarities in morality tales to occur across cultures.

4. STRUCTURE OF THE MUSICAL

In a 1991 PBS interview, composer and lyricist, Stephen Sondheim, stated the impulse to create Into The Woods was borne from his and director/book writer James Lapine’s desire to write a “fairy tale quest musical”. Like many of Sondheim’s other creations, the narrative ventures into the lighthearted, funny, and dark all at once. Into The Woods is written in a two-act structure. Act I is a container for the characters’ quest narratives in which they achieve their hearts’ desires while Act II questions what happens after each has achieved their “happily ever afters.”

Act I is a container for the characters’ quest narratives in which they achieve their hearts’ desires.

Act II questions what happens after each has achieved their “happily ever afters.”

The musical begins with The Narrator speaking quintessential words found in many fairy tales,

“Once upon a time…”

The Narrator then soars into the lives of some of the most recognizable fairy tale characters. There are some characters created by Sondheim and Lapine such as The Baker and The Baker’s Wife whose desires are at the center of the story. Still, nostalgists and light readers will recognize the plots of the following tales: “Cinderella,” “Jack and the Beanstalk,” “Rapunzel,” and “Little Red Riding Hood”. The creators poured over varying versions of the aforementioned tales and chose specific details from each that would come to life in Into the Woods. Since the creators wanted one theme to be self-discovery, the details selected from the age-old tales possibly gave the characters a sense of self-awareness and agency, or shed new light on their plights. This is specifically true for Cinderella and Rapunzel who both question their desires to remain with the princes who rescue them.

So, why the setting of the woods in this fairy tale musical quest?

Obviously, the woods are a constant in fairy tale lore. Sondheim and Lapine are not the first, and surely will not be the last to realize the opportunity for adventure in the woods. Over and over, this setting has been used as a metaphor for the unknown and growth. That being said, one characteristic of a quest is that an unassuming hero journeys into an unknown world for tangible objects that prove worth in their families or societies. While on a physical journey, the hero gains new knowledge and a revived sense of self-awareness. Placing the characters in a dark and dense forest invites danger, privacy, and an air of secrecy the characters would not have in the confines of their homes.

The Narrator

The Baker and The Baker’s Wife

Jack and the beanstalk

Little Red Ridinghood and The Wolf

Cinderella and her wicked stepsisters

Each of the main characters in the ensemble makes a self-discovery before the end of the musical. This gives insight into another common characteristic of a quest: the return home with a boon. After making discoveries about themselves, each of the characters must decide what to do with their newfound information. It is not long before the characters and audience realize they must rely on their boon or “self-discoveries” to survive a danger that threatens to destroy them all.

While Into The Woods holds fast to some traditional characteristics of musicals such as the two-act structure it offers a remix of ideas. Early in the creative process, Sondheim sought to bind each character to a particular type of music. Although he did not fully bring this idea to life, the critique of the all-encompassing phrase,

“happily ever after”

is clear in the musical. Combining the characteristics of quests, fairy tales, and musicals makes Act I of Into The Woods a delightful work of art for young and old to enjoy while Act II implores a critique that mature audiences members can reflect upon.

5. The Authors

STEPHEN SONDHEIM (1930-2021)

Composer and Lyricist, Into The Woods

In the year 2021, the world bid farewell to musical theater giant, Stephen Sondheim.

A self-described “city boy” Sondheim lived much of his life in or around New York. In an interview, he stated, “I’ve lived my entire life in twenty square blocks”. Yet his musicals have graced stages around the world. A few memorable ones (Into The Woods, Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, and, most recently for a second time, West Side Story) were captured in film and gracing the silver screen. Some of Sondheim’s other memorable works are Assassins, Follies, A Little Night Music, and Company which is currently enjoying a “gender-bent” revival run on Broadway.

Sondheim’s parents divorced when he was young. He split his summers between his mother and father’s homes. His mother, Etta Janet, who he once described as a “celebrity collector”, summered in a home three miles away from Oscar Hammerstein (The Sound of Music and Oklahoma!). Sondheim, who did not have an amicable relationship with his mother, found a nurturing environment in the Hammerstein household. He credits the relationship with Oscar’s son Jimmy and the Hammerstein family, in general, as being a springboard for his career.

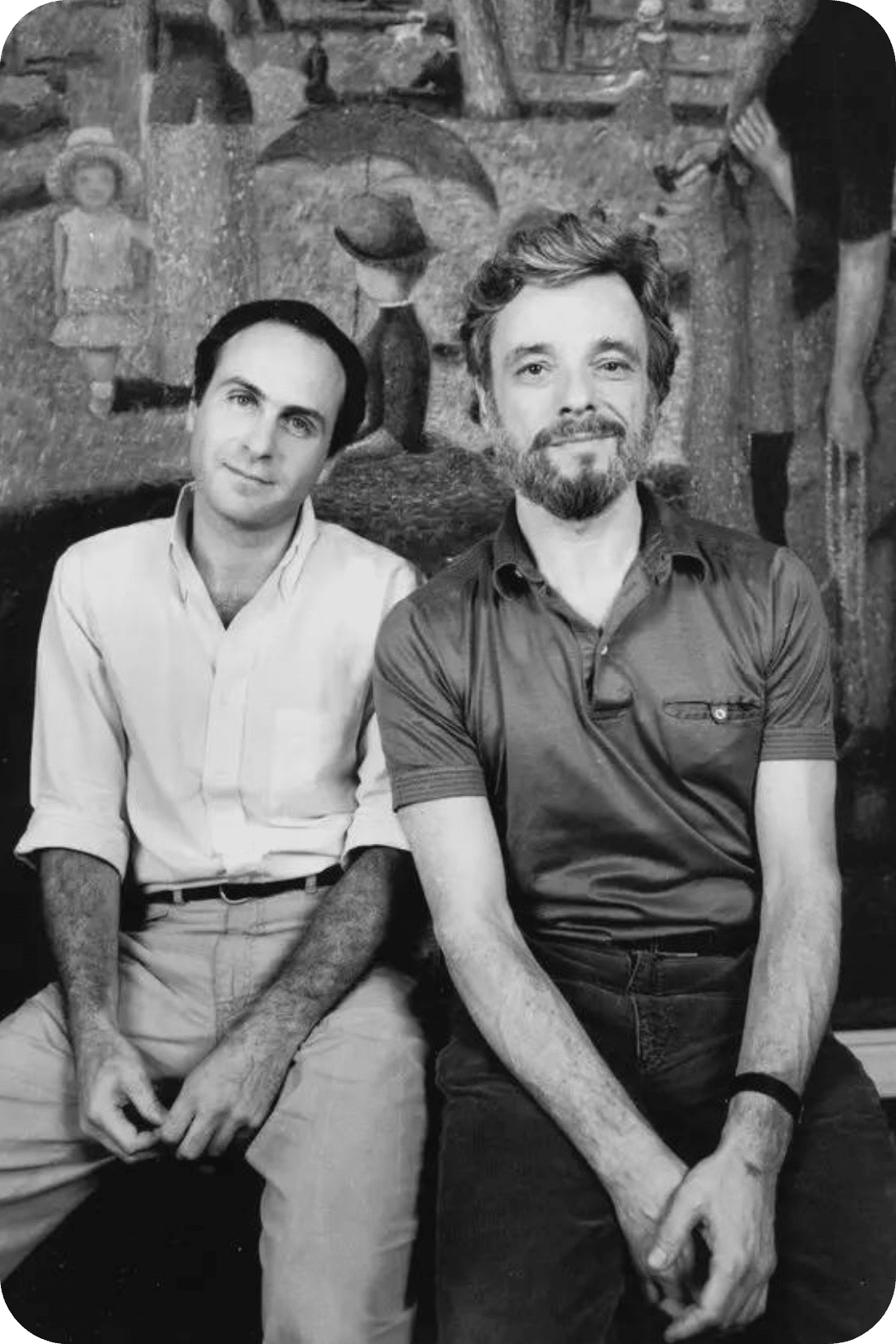

JAMES LAPINE (1949-)

Book Writer, Into The Woods

Lapine was born in Mansfield, Ohio, the son of Lillian (Feld) and David Sanford Lapine. He graduated from Franklin and Marshall College in 1971.

Lapine did graduate study in photography and graphic design at the California Institute of the Arts, where he received an MFA in 1973. He was a photographer, graphic designer, and architectural preservationist, and taught design at the Yale School of Drama. At Yale University he wrote an adaptation of and directed Gertrude Stein’s Photograph, which was produced Off-Broadway at the Open Space in SoHo in 1977. He went on to write and direct Off-Broadway plays and musicals, directing composer William Finn’s March of the Falsettos in 1981; the musical won the Outer Critics Circle Award for Best Off-Broadway Play.

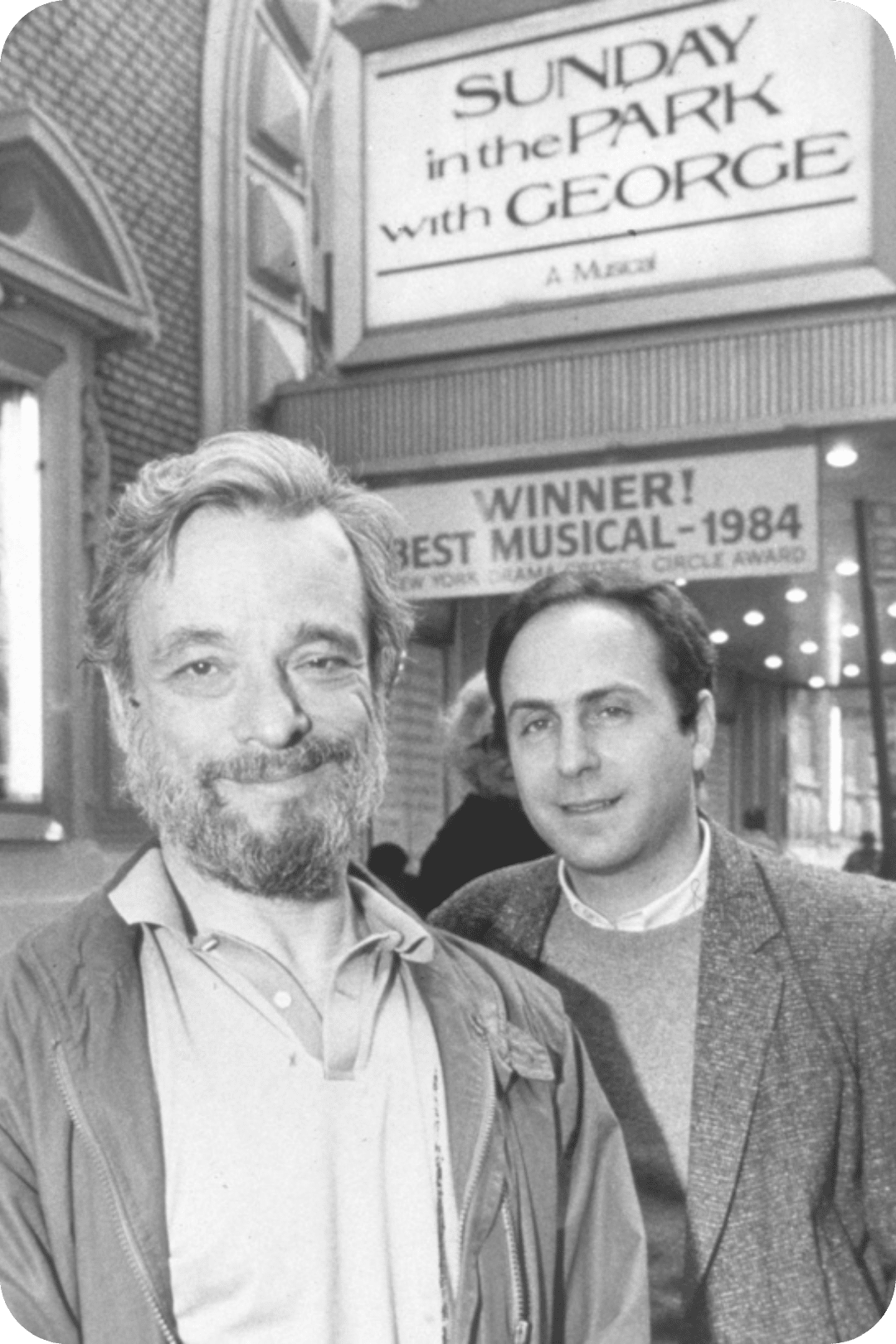

In 1982, Lapine was introduced to Stephen Sondheim. The pair developed Sunday in the Park with George. Lapine wrote the book and directed it. Sondheim created the music and lyrics. The play was first produced Off-Broadway in 1983 and moved to Broadway in 1984. Their next musical was Into The Woods, which premiered on Broadway in 1987, for which Lapine won the Tony Award and the Drama Desk Award for Best Book of a Musical.

6. Important Dates in the Production’s History

1982

Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine meet.

1984

Sunday in the Park with George, a musical by Sondheim and Lapine, opens on Broadway in the Booth Theatre.

JUNE 9, 1986

Sondheim and Lapine workshop Into The Woods at Playwrights Horizons.

DECEMBER 4, 1986

Into The Woods opens at The Old Globe Theater in San Diego, California. It runs for 50 performances.

DECEMBER 4, 1986

Into The Woods opens at The Old Globe Theater in San Diego, California. It runs for 50 performances.

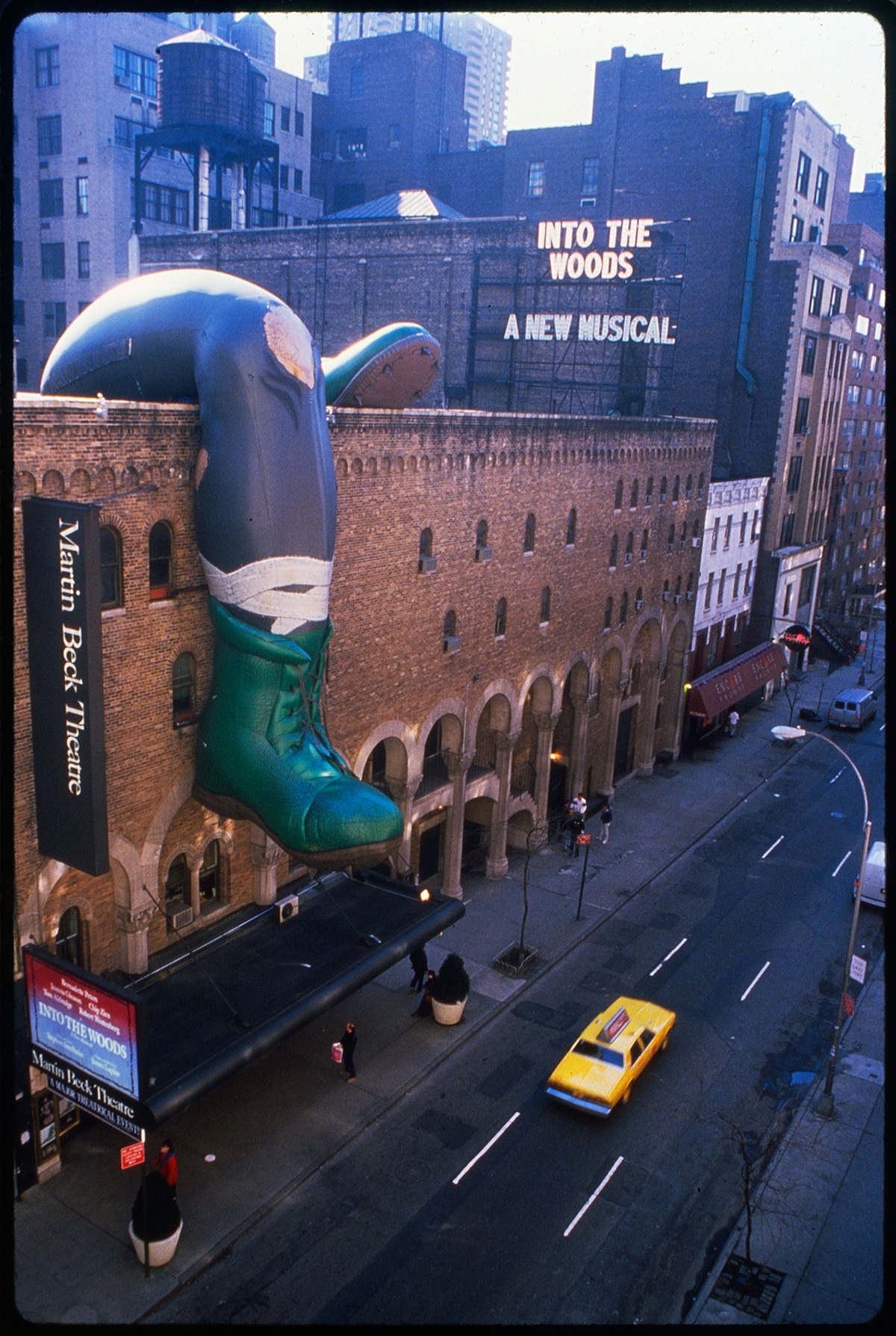

NOVEMBER 5, 1987

Into The Woods opens on Broadway in the Martin Beck Theatre.

1988-89

The show goes on a national tour with a residency at the Kennedy Center in Washington DC.

1990

The original West End (London) production opens at Phoenix Theater on September 25 and runs for nearly 200 performances.

2014

Walt Disney Pictures released a film adaptation of Into The Woods in 2014.

7. Into The Woods Trivia

1. Some say that the relationship between Jack and his mother is based on which of the following relationships…

a. Lapine and his partner

b. Sondheim and his partner

c. Lapine and his mother

d. Sondheim and his mother

2. Which of the following is a musical that Sondheim and Lapine did not collaborate on?

a. Assassins

b. West Side Story

c. Into The Woods

d. Sunday in the Park with George

3. Which theater premiered Into the Woods?

a. The Booth Theater on Broadway

b. The Old Globe in San Diego

c. Arkansas Repertory Theatre in Little Rock

d. Looking Glass Theater in Chicago

4. Which of the following fairytales is not included in Into the Woods?

a. “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs”

b. “Cinderella”

c. “Rapunzel”

d. “Jack and the Beanstalk”

4. Which character in the musical is an original creation of Sondheim and Lapine’s for Into The Woods?

a. Milky White

b. Rapunzel

c. The Baker

d. The Unicorn