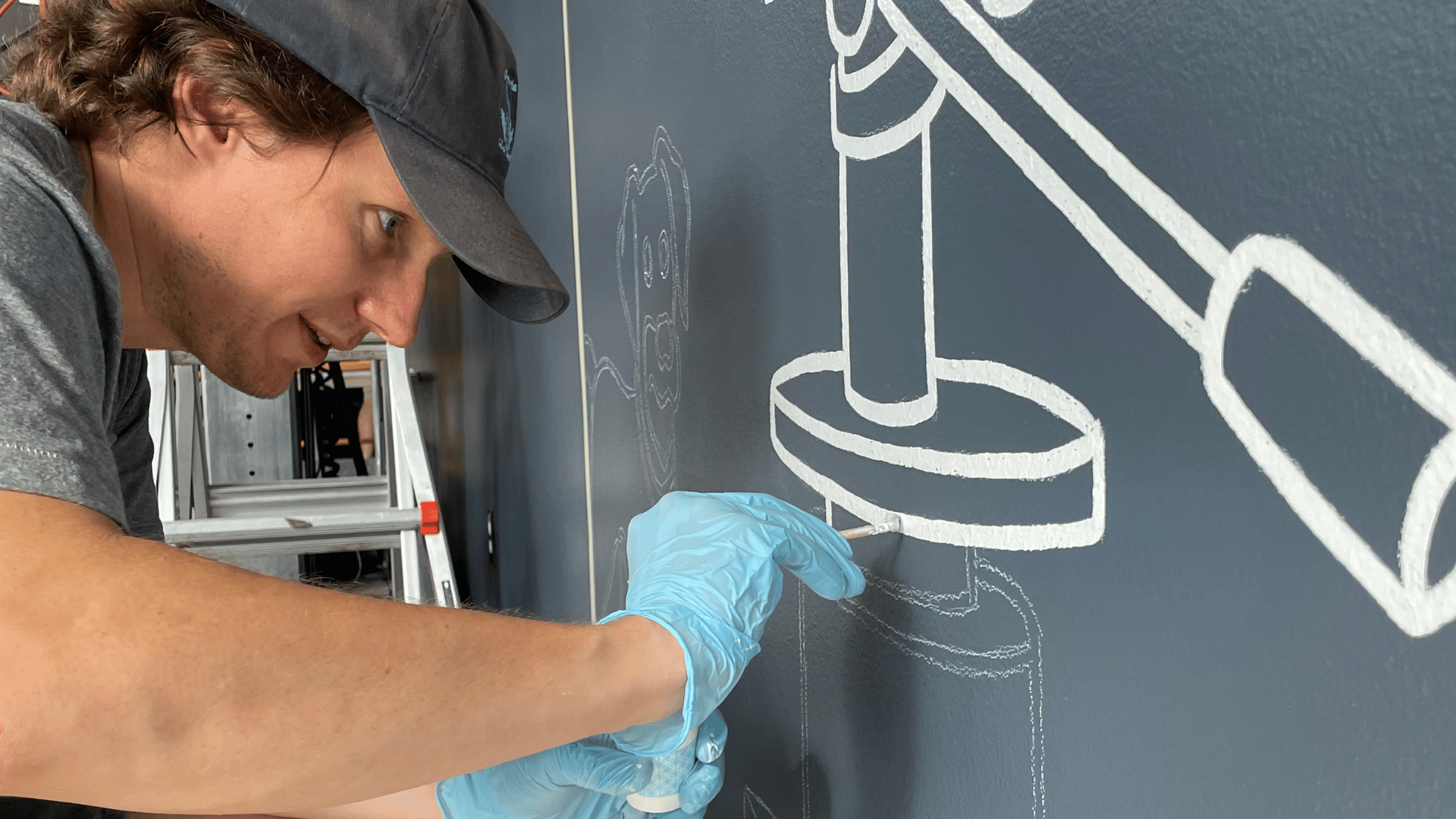

“Table Work”

a mural by Layet Johnson

“Table Work” is on display in the lobby of the Arkansas Repertory Theatre now through June 2023.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Layet Johnson was born in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1985. He received his MFA from the University of Georgia and a BA from Hendrix College. He has held fellowships at Vermont Studio Center and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. Johnson is the author of two comicbooks, Sick Day and Confidence, and co-created Pizza Therapy with Dan Gold. He has had solo exhibitions at the Thea Foundation (North Little Rock), Pina (Vienna), UA Little Rock, Institute 193 (Louisville), and Good Weather (North Little Rock/Chicago). www.LayetJohnson.com

ABOUT THE MURAL

“Table Work” is a forty-by-seventeen-foot mural designed for the 2022-2023 Arkansas Repertory Theatre season, representing images from Every Brilliant Thing, Guys & Dolls, Laughter on the 23rd Floor, Little Shop of Horrors, and Clyde’s. Named for the process of script reading by actors around a table, “Table Work” denotes similarities in writing, drawing, and reading as critical creative forms. Comprising a loose grid or “list” of 75 stand-out images noted by the artist in his read-through of the plays, “Table Work” represents the entire season as well as the visual nature of storytelling itself and the imagination required in theatre, particularly in minimal productions like the season’s opener, Every Brilliant Thing.

MORE ON EVERY BRILLIANT THING

At the center of “Table Work” is one image from Every Brilliant Thing, a record featuring a cartoon frog by Daniel Johnston whose song, “Some Things Last a Long Time,” the play mentions (the image is also a nod by Johnson to cartooning itself). The musician Daniel Johnston, whose songs are often heart-wrenching, is also known for his imaginative, colorful, and cartoonish artworks.

Every Brilliant Thing centers its own “list” as its central theme and its story is a walk-through in self-realization, narrated by a single actor and helped by the audience in forming a long list of things that make life brilliant. In “Table Work,” Johnson was given liberty just as audience members are in Every Brilliant Thing, to select his favorite things. Time is another theme shared by “Table Work” and Every Brilliant Thing, whose lead actor presents his entire life to the audience and in doing so questions meaning in life and death.

Like the play, “Table Work” incorporates its own unique timeline. As the season unfolds, each play’s objects will be colored in until it is finally erased. In creating artwork for the theatre, Johnson found that this temporality informed the work, allowing him to work playfully while thinking deeply about how to draw and symbolize a long list of objects. Like Daniel Johnston’s song, plays and artworks don’t necessarily last a long time, but pay close attention and they can be permanent in your memory.

“Every Brilliant Thing finds a perfect balance between conveying the struggles of life, and celebrating all that is sweet in it.”

A CONVERSATION WITH THE ARTIST

What was your process for choosing all of the items?

Typically as an illustrator, I ask the client to give me their list of what to draw, which I then draw up and do rounds of revisions until we get it how they like. So I was surprised and thrilled when Will Trice, The Rep’s Executive Artistic director, told me he wanted me to read all of the plays and come up with my own list, making the mural my own interpretation. This made it way more fun. But I hadn’t read a play since college, and even then it was mostly from Roman mythology.

Reading the plays was strange at first, but after a few pages you can detect each character’s voice and point of view really rapidly, and reading the plays was a breeze. To pick the images, I simply kept a pen with me and circled words and sentences that stood out. Then after finishing it, I’d go back and reread each item I circled and pick my top 10 or 12 objects.

Once I did them all, I met with Will and we discussed major themes in each play, which helped me to finalize my selection by picking out the most important things to draw. Ultimately I tried to select simple objects that would stand out to other play readers and watchers, things like a pizza or a dog or a gun.

In reading the plays, were there any moments or images that really grabbed you?

I wondered about this because I wanted to pick out the right images. Would the images that grabbed me be the same that grabbed others?

One of my favorite authors, Haruki Murakami, talks about the Russian writer Anton Chekhov a lot. I think Murakami mentioned “Chekhov’s gun” once, which is known as a rule in storytelling. It goes that if a gun is mentioned or shown in a story, it has to be used later on. It’s like a foreshadowing device. So I ended up drawing all of the guns mentioned in the plays, which felt weird because I don’t like guns. But I feel like they’re the types of images that appear in our dreams. They have psychological weight.

Another fun object to draw was the bible quote sign from Guys & Dolls. It said “there is no peace unto the wicked. – Proverbs 23.9” and in the play, Sky Masterson says that the line is really from Isaiah, so Sarah Brown just crosses out Proverbs and writes Isaiah. Without really analyzing why the playwright did that, it was a pretty hilarious moment, and as a sign-painter I loved designing my own cartoony version of it.

What are some of the elements you think about when creating a large-scale mural like this?

Thank you for asking! Elements are a design term, so to answer this correctly I have to nerd-out a little on formal art theory.

My art background is in drawing. I’m not what they call a “painter’s painter”, meaning I like hard lines and flat colors, not thick paint and blending. I’ve also learned to paint murals at the same time I’ve learned to paint signs, and in studying hand-lettering I’ve found similarities in modern art and typography, namely through line. In hand-lettering, lines are either vertical, horizontal, diagonal, arced, or s-curves. All letters are broken up into these five basic line forms otherwise known as strokes.

After painting a bunch of signs, I began drawing in this way too. So if you look at my drawings in the mural, you can see where the brush starts and stops, where it picks up and sets down. I do this with my pen too, when I draw the artwork first. And when I project the artwork, I trace both sides of the line and all of the intricacies and accidents in it.

I want the mural to look like a scale replica of one of my drawings. It should be deceiving that way, as if you’re looking at a huge cartoon sketch on the wall. But cartoons are deceiving too. While they look simple and fast, they’re often the result of laborious research, planning, drawing, erasing, and tracing. They’re a lot of work to produce something simple and effective, that work like letter forms, where the point is to relay information, or language, as quickly as possible.

Another word for this in art is “economy.” Picasso was known for this. He did a lot with a little. Ernie Bushmiller is most known for it in cartooning. So when I talk about formal art theory, I’m thinking about conceptual artists like Sol Lewitt who made whole bodies of work just studying what you can do with those five line forms. His work was never representational at all, like Picasso’s, and studying his work, even though it happened way after early abstract painting, is like a textbook for understanding abstract art, at least from a formal design point of view. There’s never any confusion about it being about anything other than shape, line, color, form, all the design elements. It’s really simple and thoughtful that way.

So when I think about creating a large-scale mural, I think about what am I scaling exactly and how do I scale it? And that all boils down to math. If you want to be good at painting murals, you have to be good at playing pool. You have to understand space and you have to know how to hold a stick. And if you like pool, you might also like Sol Lewitt.